All around the developed part of the world there is a frenzy about replacing incandescent lamps with compact fluorescent lamps, or CFLs, as they are called. What is the reason for this frenzy? Could it be the tiny amount of energy that they allegedly save?

The European Union is in the process of banning the bulb. A growing list of countries are doing the same or have already done so. Although discouraging the use of a device is perfectly OK, we rarely go so far as ban it. We usually ban things such as chemicals that are immediate dangers to our health or to the environment. Ironically, Compact Fluorescent Lamps (CFLs) would make good candidates for such a ban, because of their toxic content. So how did we reach this situation where states are actually banning an entirely innocent device such as the light bulb? Below I go on to explain why the (alleged) energy savings are almost negligible, and I present dangers that arise from the use of CFLs.

The savings in perspective

There are claims that if we replace all the world’s incandescent lamps with CFLs, then something like 270 electric power plants of 0.5 GW each will close. I don’t know how this number of 135 GW has been calculated, but it’s not far from my estimation of 150 GW (assuming 80% savings, which is optimistic, and no increased energy for lamp manufacturing, which is false).

CFLs need considerably more energy to make (and to recycle) that incandescents. Therefore, in order to find the true energy savings, we would have to add the energy consumed by the lamp in its lifetime to the energy required to construct and destroy it, and divide the result by the lamp’s lifetime. This would give us the true wattage. But since I have no hard data on this, I will assume that the replacement of all the world’s incandescents will save 150 GW.

The thing is that sometimes percentages matter. 270 electric power plants may seem interesting, but there are more than 50,000 thermal power plants on the planet. More specifically, 150 GW is about 1% of global power consumption. It’s not negligible, but it’s not anything huge either. It’s 1%. It’s certainly very different from the impression created by the advertised 80% savings.

In addition, sometimes absolute numbers matter. Whereas a CFL allegedly saves 80% when compared to an incandescent, a small car saves 20% when compared to a large car. But if you were asked whether you’d want a 20% discount in your rent or an 80% discount in your water bill, you’d probably choose the 20% in the rent. It turns out that if those who have large cars changed them for small cars, we would save as much energy as they can (allegedly) save by replacing their lamps.

Why, then, don’t we ban large cars? If people are entitled to drive a car for fun, or to go to the cinema, or to have a large TV, or to choose the temperature they want their home to have, or to fly business class, then why take away my freedom to choose the light that I want? Why force me use a lamp that produces a strange spectrum rather than the pure light of the bulb?

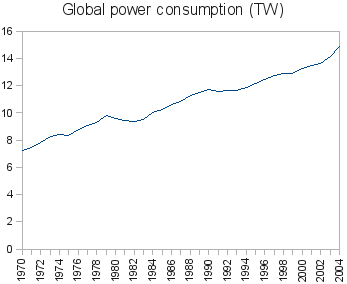

While saving 1% of global power consumption is interesting, again we should be careful not to create false impressions. There is not going to be any reduction, i.e., you should not expect the 15 TW of global power consumption to become 14.85 TW because of the ban. This is because the power we consume continuously increases, as you can see from the following graph.

Therefore, no power plant is going to close, of course. It is true that if we managed to save 150 GW of power, there could be some delay in the construction of new power plants, because there would be a minor, temporary recession in the rate of increase. In fact, the recession would be so minor that it would hardly be visible at the scale of the graph above.

Therefore, all the frenzy by environmental organisations, lamp manufacturers, politicians, and citizens about replacing bulbs is about an (alleged) minor, temporary recession in the rate of increase of global power consumption; a recession so minor that it would hardly be visible if plotted at a reasonable scale. We want not only to encourage, but to force people throw away the light bulb, a simple device consisting of harmless materials, that could easily exist 200 years from now no matter what happens at technology and civilization, and replace it with a complicated system with toxic content, that cannot be dimmed with traditional dimmers, and that takes some time to reach its luminosity and is therefore inappropriate for some applications such as corridors and staircases, where you need the light immediately but only for a few seconds.

Interestingly, I doubt even that we are going to actually have these alleged savings of 150 GW, because people have the tendency to use as much energy as they can. If you replace your lamps with CFLs, you will probably be less careful about switching them off when you don’t use them, because you know that they consume much less power. The phrase “lights will never go out” in Siemens’ press release reflects a way of thinking that is dominant in society. We use more and more light, wanting our cities to be more and more luminous. As a result, we have destroyed the night sky, whose beauty has been occupying poets for millenia, whereas words like “twilight”, that were once common in our vocabulary, today are strictly academic. Unfortunately, it is not only the night sky that we are missing, but the beauty of the night itself. That we like darkness is obvious by the fact that, if the light of a street lamp gets too much into our room, we close our window blinds in order to sleep; that we like to go to dimly lit restaurants and bars; and that we love the dim light of candles and fireplaces. And yet the tendency today is to flood our cities with artificial light and eliminate darkness altogether. In this respect, CFLs may have a bad environmental impact, because having to pay for the energy can stop us from using too much light; if CFLs are as cheap as it is advertised, this will lift this economic obstacle to light pollution, while the increased usage may mean that the true energy savings may be considerably less than 150 GW.

In summary, all the fuss about CFLs is about a debatable 1% of alleged energy savings, accompanied by toxic waste, light pollution, and worse light quality.

Reasons for the frenzy

Certainly profit is one of the driving forces behind the ban. It is hard for me to believe that the marketing campaign by Siemens is because of their determination to save the environment. I can make some guesses about why CFLs are profitable for large lamp manufacturers. First, they are way more expensive. They appear cheap to you because they are subsidized. My second suspicion is that while small manufacturers have the technology to make incandescent lamps, and therefore compete with large manufacturers, they probably can’t make CFLs. Therefore, these guys will likely go out of business and the large manufacturers will get their customers. My third suspicion is patents. CFLs have about 20 years in the market. This means that the first patents are expiring. But 20 years ago they were much worse than today; they produced very bad light, and they were huge in size. Clearly there have been many developments. Probably the newest patents are no more than 5 years old, which means they will last for at least another 15 years. This means that any small manufacturers who make CFLs will have to pay patent fees to the large manufacturers, who own the patents.

If someone profits, someone else loses. And the one who loses is usually you. In our case, the small manufacturers also lose. But the result can be a state-enabled cartel of manufacturers: the state has granted these patents, and the state has decided on the ban. Therefore the state enables the cartel. Cartels raise prices. Whether you can feel the higher price when you buy the CFLs, or whether it is included in your taxes in the form of subsidy for CFLs, you are certainly paying more.

But I don’t think that profit can explain everything. I think that the manufacturers, at first, used good marketing, like the alleged 80% savings, to convince consumers to buy the product, and then the environmentalists took it differently, and then the manufacturers saw the opportunity and jumped on. Huge momentum was created when the manufacturers built upon the environmentalists who built upon the manufacturers.

Further reading

The Professional Lighting Designer’s Association has more material, including things that you can do to stop the frenzy. They have also written a report that provides good background.

Other interesting opinions can be found in American Thinker and in techmind.

Rod Elliott has written a huge article that explains incredible details about CFLs.

Appendix

In this appendix I provide support for various claims that I have made in the main text above.

How much energy can be saved

My estimation about how much energy can be saved if all the planet’s light bulbs were replaced by CFLs: Lighting accounts for 8.8% of power consumption at home. This is true for the United States, and in the absence of more data I assume that the same applies for the rest of the world. Household consumption accounts for 15% of global power consumption. I assume that all this 15% is electric power, although households also use natural gas and oil. Therefore lighting is 8.8% of 15%, that is, 1.3% of global power consumption. If I take natural gas and oil in my calculations, the result will be even less.

I make the rough assumption that all household lamps on the planet, and only those, are incandescent. This is wrong of course, but I think it is not very far from the truth. While some homes have CFLs and some businesses have incandescents, I think that, approximately, these will be evened out, and that we can roughly assume that the 1.3% above is all incandescent light. Therefore, if all incandescents are replaced by CFLs, the alleged savings are 80% of the 1.3%, or 1%.

According to the EIA (11.1, World Primary Energy Production by Source, 1970-2005), from which the global power consumption chart above is also derived, the total amount of energy consumed by the planet in 2005 was 4.6×10¹⁷ BTU, or about 4.6×10²⁰ J, which when divided by the number of seconds in a year gives an approximate average of 15 TW, the 1% of which is 150 GW.

The consumption of cars

I have claimed that large cars consume 20% more than small cars. This is personal experience. I had a 1.4-litre, 860-kg Renault Clio, and according to my measurements its consumption was less than 8 litres of gasoline per 100 km when used in Athens. In contrast, I can see at the computer of my father’s Renault Scenic (must be 1.6 litres, I’m not certain) that its average consumption is more than 10 litres per 100 km. Therefore, the 20% is quite optimistic.

For a car that travels 10 thousand kilometres in a year, the 20% is about 2 litres of fuel per 100 kilometres, or 200 litres for the 10 thousand kilometres, or 0.55 litres per day. One litre of gasoline has energy of about 35 MJ, therefore we consider that a small car saves 0.55*35 = 19 MJ per day. Now if you have four 100 W incandescents at home and leave them on for 4 hours per day, this is 1.6 kWh or 5.8 MJ. Replacing those with CFLs will allegedly save 80% of that, or 4.6 MJ. But in order to be fair, we need to divide this with the efficiency of power plants, because a typical power plant, in order to produce 1 MJ of electricity, will consume from 2 to 3 MJ of fuel. I assume an average efficiency of 0.4, which means that the savings are 4.6/0.4 = 12 MJ.

Other issues

That CFLs are subsidized can be found at Gad Giladi’s report.