(A presentation I made on 7 November 2015 at a Greek free software conference, the FOSSCOMM 2015, TEI of Athens)

(A presentation I made on 7 November 2015 at a Greek free software conference, the FOSSCOMM 2015, TEI of Athens)

Although my subject is Enhydris, we will only take a short look at it towards the end. We will first talk about development methodologies and about good and bad uses of technology.

Developing a great project

I am under the impression that unit testing is still considered something exotic by many developers. I think that this has to do with a certain kind of provincialism that we have. I’m not talking about Greece, but about many developers all over the planet who don’t work on great projects like Python and Django. We have a certain kind of provincialism and we say “these people at Python, when they write code, they always unit test, and they always review”. Since they always unit test and they always review, why don’t we also do it in our own projects? Is it that we are smarter? Probably not. Are we dumber? I don’t think so. It is therefore an issue of will, given that we have the ability. Whether our project will become great is a matter of choice. And I chose, on the 14th of past October, that Enhydris will become great; no, that it is great. We therefore follow development methodologies similar to Django’s; we always unit test and we always review the code. And if, now that we are temporarily unfunded, Stavros is unable to help, and if I stay alone, I will still be submitting the pull requests to github, and I will be reading my code yet another time, and I will be writing comments to myself, and myself will subsequently be taking my comments into account before pulling my commit to the official repository.

Enhydris is therefore the project you want to contribute to if you want something great but Python and Django seem too crowded.

Bad use of technology

The next issue is about good and bad technologies. If while I’m talking to you my dad calls me, I will stop communicating with you. If you call me while I’m talking to my dad, I will stop communicating with my dad. So here we have this paradox, this device, which is supposedly a communications device, often destroys communication. You live this every day. It doesn’t only destroy communication between people, but also between you and the rest of the world. In this figure, Deutsche Telekom’s advertiser has given the spirit of the age nicely, and he considers it to be a good thing (because he profits from it). However, I think it’s a bad thing, because this woman does not communicate with her environment, she doesn’t see the people around her, she doesn’t see the platform and the trains, and she is detached. Now, you will tell me she sees these every day, and it is frustrating to wait for the train every day, and it is nice to have another thing to do. However this girl will not stop here. She will continue to play with her smartphone when she enters the train, when she gets out of the train, when she walks on the street, and even when she talks to you and has her smartphone in her pocket and does not touch it, even if she doesn’t have this nervousness on her fingers that some people have and seek for their smartphone as if it were a cigarette, the mind still is anxious about what is happening in the pocket. You live in this and you understand what I’m talking about. And as a result this device, whose purpose is, supposedly, communication, isolates us from real life if we aren’t serious about controlling it. This is a bad use of technology.

Good use of technology

I will now show you a good technology, and I want you to think about where the technology is.

The plant draws water from the soil and transpires it through its leaves. When there’s much water in the soil, the plant draws much water and transpires much water. When the water is less, when, that is, soil moisture is lower, and the plant can’t draw water that easily, it transpires less. We then say that it is in water stress. If the plant is in great stress, it will yield little; but if it has ample water, its fruit may be less tasty. It’s better for the plant to be in the right amount of stress in each phase of its development. For example, when it’s young it may need much water, when it grows it might be best if it has a little stress, when it flowers it might need less stress, and so on. If this is done correctly then the fruit has the right amount of sugar.

The plant draws water from the soil and transpires it through its leaves. When there’s much water in the soil, the plant draws much water and transpires much water. When the water is less, when, that is, soil moisture is lower, and the plant can’t draw water that easily, it transpires less. We then say that it is in water stress. If the plant is in great stress, it will yield little; but if it has ample water, its fruit may be less tasty. It’s better for the plant to be in the right amount of stress in each phase of its development. For example, when it’s young it may need much water, when it grows it might be best if it has a little stress, when it flowers it might need less stress, and so on. If this is done correctly then the fruit has the right amount of sugar.

We therefore install meteorological stations in our field and we measure rainfall, temperature, humidity, wind speed and solar radiation, and from the rainfall measurement we know how much water goes in, whereas from the other variables we calculate the evaporation and transpiration and we know how much water goes out. If we know the soil type we can also estimate how much water goes out through deep percolation. We also plant some soil moisture sensors to have better data. Based on all this, our software can control the electrovalves and provide the right amount of water so that our plants have the right stress all the time.

In this way we can save much water, such as 85%, but it’s not only about saving water, it’s also about improving the product. Water is of course only one of many factors a wonderful tomato needs, but it is equally important as the other factors. This method is state of the art, and has only recently started to be used for wine grapes in Italy. I haven’t yet heard about someone using it for tomatoes.

For me technology is good when it is invisible. It is good when it helps me connect to nature but at the same time stays out of my way. I can connect to nature not only by visiting a spring in the countryside, but also eating a beautiful tomato or going to a bar and talk with another person. A few days ago I met with my friend Joanna and we discussed about all that, and our smartphones didn’t bother us, at least not much, and we both had each other’s full attention, and we were drinking some wonderful wine. If it weren’t for technology, we would have been unable to meet in that evening.

Enhydris

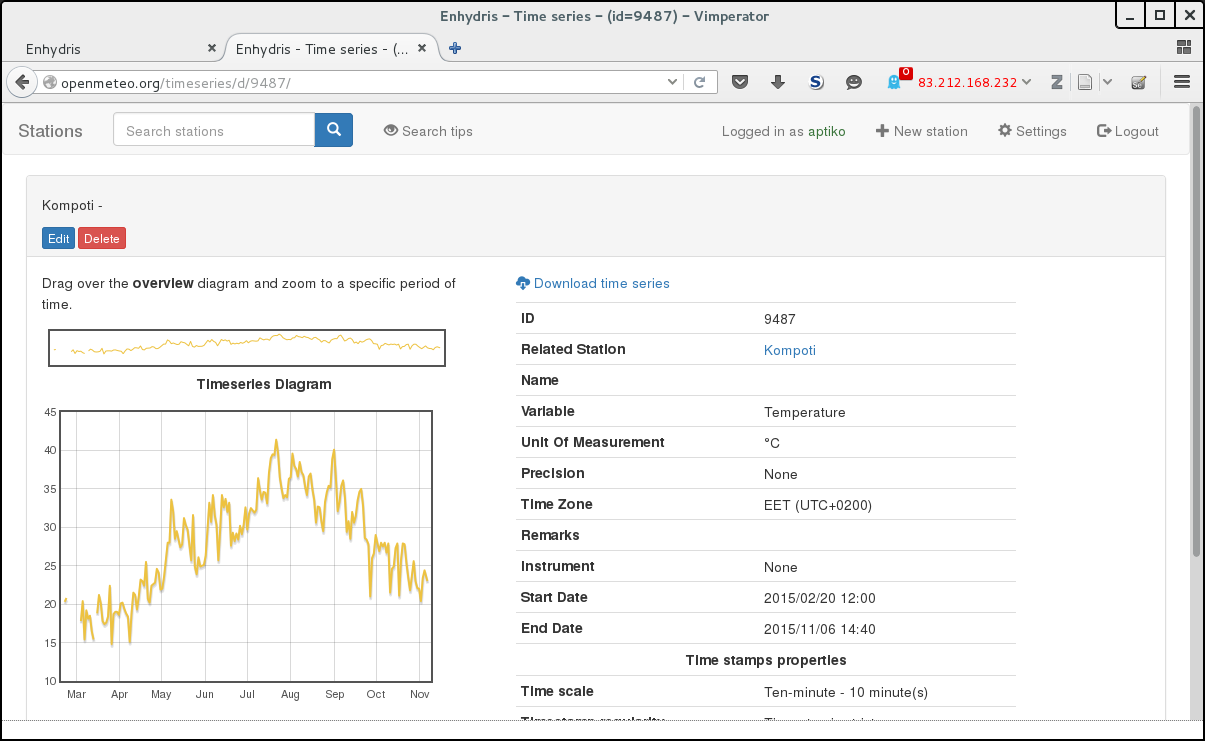

I will now tell you about Enhydris. I talked to you about measurements; rainfall, humidity, temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, soil moisture; all these are measurements. We usually setup the system to make one measurement every 10 or 15 minutes. If you have one hundred meteorological stations, this amounts to several million of measurements each year.

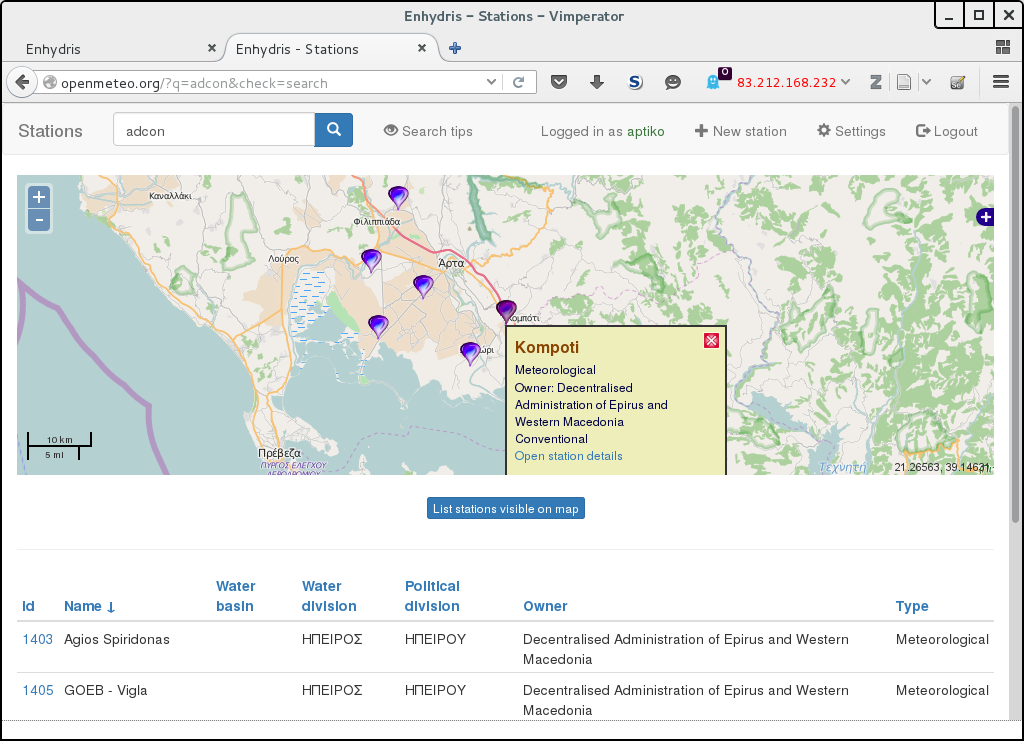

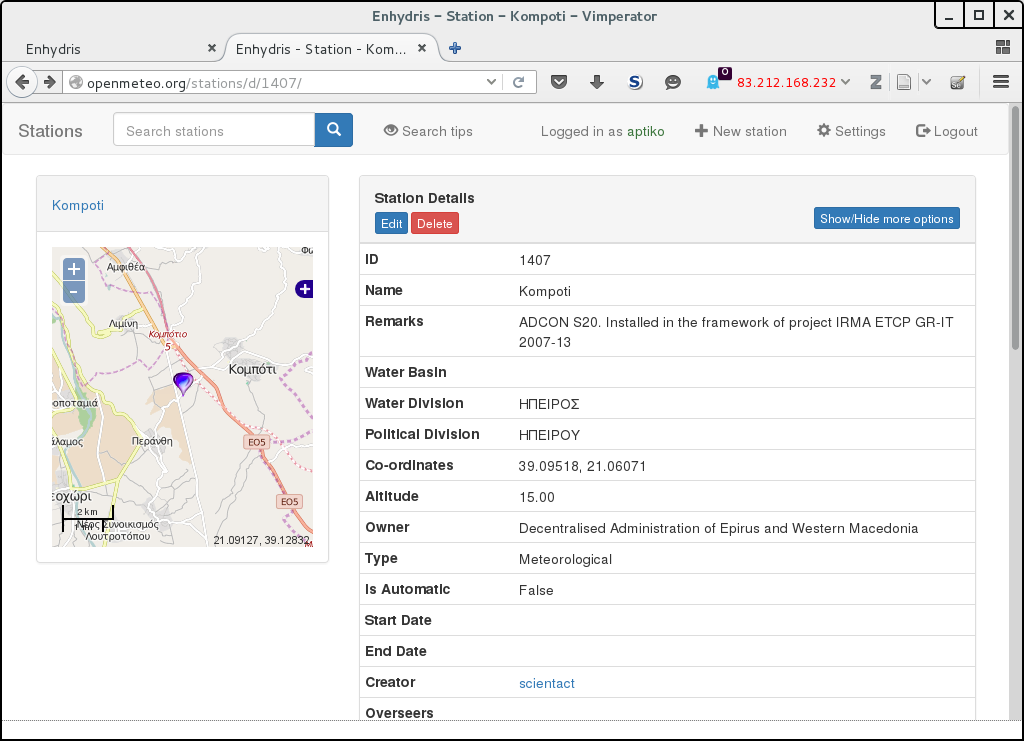

I will now tell you about Enhydris. I talked to you about measurements; rainfall, humidity, temperature, solar radiation, wind speed, soil moisture; all these are measurements. We usually setup the system to make one measurement every 10 or 15 minutes. If you have one hundred meteorological stations, this amounts to several million of measurements each year.  Enhydris is simply a database for measurements. It shows the meteorological stations on a map, you can click on a station and get some information, you can click for more information, there’s a list of time series at the bottom, not visible here, where you can select, say, temperature, and you can see the measurements in a chart or download all of them by clicking on a button.

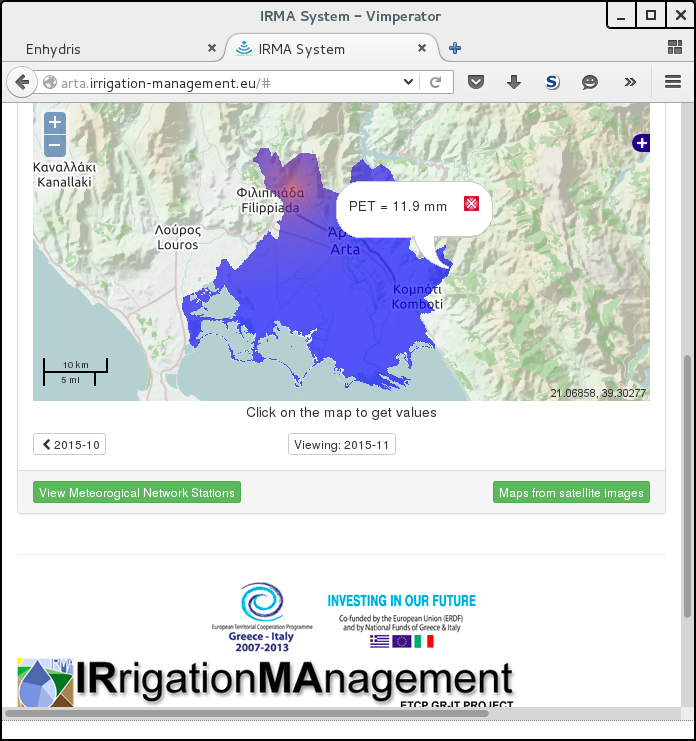

Enhydris is simply a database for measurements. It shows the meteorological stations on a map, you can click on a station and get some information, you can click for more information, there’s a list of time series at the bottom, not visible here, where you can select, say, temperature, and you can see the measurements in a chart or download all of them by clicking on a button.  That’s all Enhydris is. It does one thing and does it well. Not as well as I’d like, but it’s OK. It also has an API, which is used by another application which takes the data from the meteorological station and uses the API to upload them to Enhydris. There are also other applications that use the API; for example, we’ve made this one for the plain of Arta.

That’s all Enhydris is. It does one thing and does it well. Not as well as I’d like, but it’s OK. It also has an API, which is used by another application which takes the data from the meteorological station and uses the API to upload them to Enhydris. There are also other applications that use the API; for example, we’ve made this one for the plain of Arta.  We have six stations, which are points, but we want information on the entire plain, so we perform a kind of interpolation between these points, that is, spatial integration. This application does something similar with what I showed you about the tomatoes; it provides the farmer with irrigation advice, that is, it tells them how much to irrigate. But this is not Enhydris, it’s another application that uses the API of Enhydris in order to get the data.

We have six stations, which are points, but we want information on the entire plain, so we perform a kind of interpolation between these points, that is, spatial integration. This application does something similar with what I showed you about the tomatoes; it provides the farmer with irrigation advice, that is, it tells them how much to irrigate. But this is not Enhydris, it’s another application that uses the API of Enhydris in order to get the data.

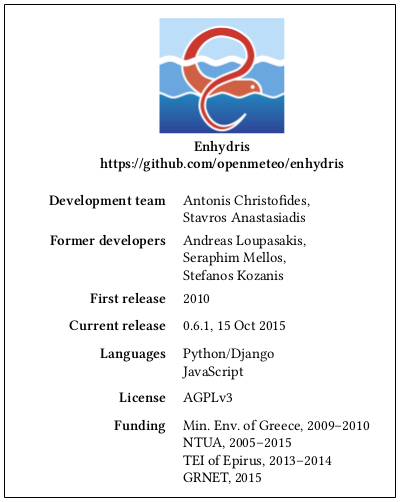

Enhydris started on 2009 and has been funded by a number of organizations. Most recently it was funded as an open technology project, which helped us fix a few things that had been bothering us for years, so we think we now have a good foundation to build more things.

The photograph of Cosmote’s advertisement was taken by me in the Athens Metro on 6 November 2015. I don’t know who is supposed to be holding the copyright. To the extent that I have rights on that photograph, I grant anyone the right to use it for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law. However, to the extent that Cosmote (or OTE, or Deutsche Telekom, or whoever this company actually is) has rights, I obviously do not have the authority to grant them.

The photograph of tomatoes is ©2012 by Wikipedia user “Spirtu”. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. See its page in Wikipedia for more information.

The rest of the pictures, and the text of the article, are licensed under the same terms as the rest of this site.